The game

The rules of the Troika

This game started in 2010: He who lends money dictates the rules. He who borrows money must adhere to the rules. Before the euro crisis, it was developing countries in particular which had to learn this from international investors, but with the euro crisis Europe too is now affected. In Portugal and Greece especially, everything the state has to offer is being auctioned off under great time pressure: waterworks, banks, beaches, airports, electricity grids, ports, palaces – even mineral springs. The first chapter highlights gamers, rules and the financing.

The Bank – Just who is the troika?

In Europoly, where people play for state property like they do for Monopoly’s streets, the role of the bank is played by the so-called Troika. At the start of the game, the bank hands out money to the EU’s crisis-affected countries. They paid €68 billion to Ireland, €270 billion to Greece, €78 billion to Portugal and finally ten billion euros to Cyprus; all after they were no longer able to borrow money in financial markets as a consequence of the eurozone crisis. Troika officials – from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the European Commission – then make sure the countries meet their targets, as specified in the rescue packages.

Albert Jäger is a nice man. He has a narrow face, wears glasses, speaks quietly and in measured tones and thus makes the discreet, modest impression you might expect from a civil servant. Hardly anyone in Portugal would know his face, but he has power. Mr. Jäger is the International Monetary Fund’s representative in Portugal and, along with his colleagues, has been responsible for making decisions on credit payments to Portugal in recent years. He helped decide how much money would be cut from pensioners‘ incomes, to what degree protection against unlawful dismissal should be relaxed and to whom government-owned companies should be sold. Mr. Jäger works for the Troika, a committee that was never envisaged in any EU treaty and yet still determines policies in the nations affected.

Every few months, IMF and Commission officials take note in „progress reports“ of what they believe is going well and in which areas the „programme country“ (a Troika term) should be trying harder. Most inspectors only fly in for a few days, and the teams consist of up to 40 people. Among the most important figures in recent years from the Commission have been Monetary Affairs Commissioner Olli Rehn and his negotiator Matthias Mors; the ECB usually sends in banker Klaus Masusch, while the IMF’s most important negotiator is Poul Thomson from Denmark. None of them stand out any more than the quiet Albert Jäger, nor do they particularly like to appear in public. The Troika has no real face.

To Southern Europe, the Troika is the embodiment of the crisis. In Greece, officials can now only work in the company of security guards. Even in Brussels nobody is particularly proud of this committee. On the contrary: The European Parliament came to the conclusion in an investigative report that the Troika and its officials are not sufficiently democratically legitimised. Jean-Claude Juncker, new president of the European Commission, has already announced his intention to restructure the Troika – despite being one of the founders of the committee as former president of the Eurogroup. It should reportedly take a different approach, be more transparent. Perhaps the IMF should also withdraw to make the whole thing a purely European project.

But still nothing is likely to change regarding the Troika’s agenda. Privatisations are a fixed component of the programme. The Europoly bank doesn’t just spend the money up front; it lends it to the parties concerned and then sets the rules of the game. Different players must borrow varying amounts of money. Others bring their own stacks of it.

The Players – Who is selling what?

For the states there are four Europoly players. The countries in which the Troika has already been deployed are Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Cyprus. They start the game with varying levels of debt. Whoever borrows the most money must also sell the most.

Both domestic and foreign investors are joining in the race for lucrative companies and properties.

The Greek player has the biggest problems. Greece has received around €270 billion in loans from the Troika, divided up into two rescue packages, since May 2010. The country is cutting pensions, cancelling unemployment benefits and raising taxes. The economy is collapsing; on its own, the government can hardly pay for anything anymore. But the borrowed money also comes at a price. In return, Greece promised – among other things – to generate €50 billion from privatisations by the scheduled end of the programme in 2016. This money is intended for direct debt repayment. However, the hoped-for €50-million return was highly over-estimated to begin with. „World’s biggest divestment programme“ is presumably no more than a gap in official calculations that had to be filled somehow. Since then, the target has shrunk to just €11 billion by 2016, and even that seems unlikely. It is the population, which now needs to save even more money than they already have, that is suffering from the consequences of these false estimates.

One year later, in May 2011, Portugal followed suit and saved itself and its banks with €78 billion in bailout money. The country promised to generate around €5.5 billion from privatisations with which to pay off debts. Portugal has become the Troika’s favourite player over the years, with the government clearly surpassing its set targets. By the end of the Troika programme in the summer of 2014, it will have generated around €9 billion and sold state-owned companies to China and an entire bank to Angola, the latter at a low price. Portugal officially leaves the bailout programme in May 2014, but must continue to fulfil its obligations via the Troika.

Click on the highlighted countries to learn more about the privatisations!

For players Ireland and Cyprus, the situation is slightly different: Ireland was hit by the crisis as early as 2010 and was the first nation to exit the programme. The country received bailout loans amounting to €68 billion and promised the Troika to generate three billion euros from privatisations. However, the only major initiative – to sell the energy and gas company Bord Gáis – has so far come to nothing. Because Ireland’s economy is shaping up well, alternative ways are now being pursued to pay off the debts. Cyprus is the most recent nation to seek shelter under the bailout umbrella. The game has only just begun for this little island. It has received €10 billion from the Troika and has committed to generating revenues from privatisations totalling €1.4 billion. The search is still ongoing for the right properties to privatise, but it will probably be the island’s ports.

By contrast, players that fall under the category of „national or international investors“ enter this game of Europoly with absolutely no debt and much capital of their own. Profits are beckoning, which is why these players also like to work in tandem. The odd local oligarch (often from a banking dynasty or an oil billionaire) and his company join forces with foreign investors. The Chinese are especially active as foreign investors. The largest private Chinese financier, Fosun, is making purchases in Greece and Portugal countries, and even the Chinese state is joining in: In Portugal, Chinese government-owned companies are buying up the energy sector. French companies are interested in the waterworks of both countries. The daughter of an Angolan despot is engineering a deal for a bank with a Portuguese billionaire. German companies are also getting involved. There is much money in play, so there is also a great deal of cheating going on in deals during this game: an advisory bank is being accused of disclosing secrets, the head of the Greek privatization fund has gone on holiday with a buyer’s private jet. There is a lot going on. But first, the rules.

The Rules – What is written in the troika contracts?

Reading the rules of the game is no fun. Defining them yourself, on the other hand, is. Privatisations are a fixed component of the Euro-stabilisation programme; the Troika writes them into every treaty. The European Commission declares itself convinced „that privatisations serve to make the economy more efficient and to reduce debts.“ They deem it absolutely necessary for countries in debt to bring in foreign investors to reinforce the economy – the idea being that the investors then put even more money into businesses and create new jobs. What this means for the game is that the state sells as much of its property as it can, to as many interested parties as possible at the highest price. This is supposed to earn the state so much money that paying should not be an issue upon returning to the game board. So far in Europoly, this has not worked particularly well.

The national governments think similarly to the Troika: the management and competitiveness of companies will be improved by privatisation. In any case they do not think the states have made very much of their property up until now. For example, Gikas Hardouvelis, former private banker and Greece’s Minister for Finance since June, says: „The state is a bad manager.“ At any rate, there are supposedly no alternatives to the privatisation programmes; the money is needed to pay off debt.

In Europoly, the players negotiate the rules with the Troika. When a state seeks refuge under this umbrella, the Troika makes a contract in the name of the eurozone nations with the country in question – a so-called „Memorandum of Understanding.“ This agreement records roughly which reforms and cuts will lead the „programme country“ back onto the right path. Further contracts and „updates“ then stipulate more precise figures and the privatisation programme is set in stone.

For the Greek player, the sales obligations sound like this: „The Government stands ready to offer for sale its remaining stakes in state-owned enterprises, if necessary in order to reach the privatisation objectives. Public control will be limited only to cases of critical network infrastructure.“ Similar declarations are also found in the other countries‘ contracts too. And what do the governments and the Troika mean by critical network infrastructure? This question remains unanswered. In any case airports, water supply, electricity companies, ports and rail transport are not included; they are all on the market.

The sale itself should be entrusted to the respective government. Although in the case of Greece, that is not exactly true. There, the people making the rules did not expect the „bad manager“ to be any better at selling. This of course has to do with the Greek government transferring by law all of its holdings to the Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF) – a trust fund especially set up for this purpose. The government is indeed nominally in charge of the fund, but has no influence on decisions. Parliament is not involved anyway. The same applies to sensitive areas like, for example, the water supply. And according to Greek legal experts, the state foregoing these „special rights“ will also mean the end of regulations that up to now have been sacrosanct to the population. This includes the ban on uncontrolled coastal building projects – breaking a taboo for the Greeks.

In Portugal’s case, the government retains more decision-making authority. With the Troika, it has decided on a list of companies to be privatised. The country has already had its own ambitous re-privatisation programme since just after the end of the Carnation Revolution of 1974, during which almost all large companies were nationalised. But not every decision was enforceable in parliament until the Troika came along. That has changed with the support of the new financial backers. Now, smaller political parties have no say in the matter. Together, the Portuguese government and the Troika included preposterous details in the contracts enabling subsequent business dealings worthy of scrutiny – such as the BPN bank scandal (see „The GO Square“).

In Monopoly, the bank is neutral towards the player. Similarly, Europoly’s Troika officials insist they put no pressure on the affected countries to privatise especially fast or intensively. But when Thomas Wieser, head of the Euro Working Group – the committee that prepares the Eurozone finance minister’s resolutions – speaks about the negotiations, it sounds more like this: „At no point did the Troika or the EU say this and that had to be sold by a certain time. But if the Greek government agrees to generate €2 billion by next year and then only has €500 million, then the money must be saved elsewhere. And that is difficult – of course it puts pressure on the recipient country.“ A promise is a promise. And it makes the question of ideal timing of the sale academic. It is written in black and white in the Greek treaty: should Greece not generate the projected privatisation revenue, then it must raise at least half of the figure by other means, i.e. even more saving. But enough about the rules; now we come to the real thing.

The Game Board

A digital dream

The Europoly board is digital. Greece is particularly keen on a smart online presence. On the Greek trust fund’s website, potential buyers can find all privatisation projects listed, nicely photographed, complete with the most important figures. Fancy a port, a nice beach or perhaps you’d prefer a waterworks? There is an additional online auction house for 1,000 or so pieces of real estate where you can start bidding right away. Portugal has not prepared its line-up quite as attractively, but buyers are even more active than in Greece.

OlD KENT ROAD – The shady deal with the bookmaker

It remains unclear to this day whether Stelios Stavridis was confident he would not be caught or if he really thought what he was doing was fine. Either way he was mistaken. At the same time, it was not by chance that the Greek trust fund chose bookmaker OPAP as their first major privatisation project. They thought of it as an uncomplicated deal with little potential for scandal – just like the first minor Monopoly streets are reasonably affordable yet popular for their reliable profits. But Mr. Stavridis, chairman of the trust fund at the time, went on vacation in a private jet belonging to billionaire Dimitris Melissianidis. In fact, this was immediately after the trust fund had sold OPAP’s government shares to a Czech-Greek fund in which that very billionaire holds a stake. The holiday was not well received, either by his fellow Greeks or the international financiers; Mr. Stavridis was promptly fired and the deal mutated into a scandal.

OPAP is one of the most profitable lottery firms in Europe. The small betting shops, specialising above all in sports betting, can be found on every corner of Greek cities. The industry is regarded as crisis-proof – not something that can be said of many sectors of the Greek economy. „People are betting less money than before, that is true“ said the manager of an OPAP shop near Syntagma Square in Athens. „But on the other hand, many more people are coming to us – all hoping for a stroke of luck.“ Nobody actually objected to the sale, because the general view in Greece is that it does not belong to the state’s core duties to run a betting firm. But it certainly was lucrative.

Opap-bettingshop in Athens (photo: ES)

Before the acquisition, the Greek government held one third of OPAP’s shares which meant that it pocketed around a third of the firm’s gross profit. In the crisis year 2011 net profits were still around €505 million. The state sold its share to Emma Delta, a fund with various investors from the Czech Republic, Russia, Slovakia and Greece. Mr. Melissianidis, one of the richest men in Greece, always appeared publicly as a representative for Emma Delta and also signed the contract. Emma Delta paid €652 million for 33 percent of the company, i.e. €6.13 per share. The purchasing agreement was accomplished in 2013 a quick deal which proved lucrative for Mr. Melissianidis and his partners. On the day of the acquisition in October 2013, the shares were already worth €9.13, i.e. around 50 percent higher than the agreed price. The shares are now worth just over €12.

So did the Greek government forgo a good price by selling too early? The fact is that despite there being other interested parties, Emma Delta was the only consortium to make a firm offer. Thus there was no bidding competition, which goes against every basic rule of successful privatisations. But Greece desperately needed to make this sale in order to hit the 2013 privatisation target of €1.3 billion. A number of other major deals had fallen through beforehand, including an attempt to sell gas firm DEPA at a high price. Therefore, further credit payments also hinged on the success of this sale.

According to the Financial Times, state prosecutors in Athens have been investigating the sale of OPAP since February 2014; they have made no findings so far. The investigation reportedly concerns a lack of transparency and possible conflicts of interests of those involved. After Mr. Stavridis‘ dismissal, the privatization trust fund and the Greek administration insisted that it had been purely for „ethical reasons“ and that the OPAP case did not need to be reopened.

The Mayfair – The multi Billion Euro deal with Athens‘ Former Airport

If you want to see the future of Athens, you need only drive 30 minutes north of the city centre. Here in Chalandri, one of the city’s richer suburbs, you will find the Golden Hall shopping mall. Because of the economic crisis, people hardly venture into this group of luxury stores boasting a golden escalator behind an illuminated fountain. Odisseas Athanasiou, manager of Lamda Development, welcomes guests on the sixth floor of this complex. His business owns this luxury shopping mall, one of the Greek trust fund’s smaller privatisation projects. This world of gourmet restaurants and perfumeries mirrors Lamda’s dreams for Athens and represents one of the biggest real estate deals in EU history. It is a Greek Mayfair with hotels which are supposed to bring in millions, all made feasible with the help of the Troika.

Lamda-CEO Athanasiou (photo: ES)

This is all about „Hellenikon“, a defunct airport in the south-west of Athens. It concerns a surface area of over six million square metres – an area six times the size of the former Berlin airport Tempelhof, with its own Mediterranean coast to boot. Mr. Athanasiou, holding an iced coffee in one hand, drew a quick sketch on his notepad before offering to show his promotional video. Computer-animated, beautiful people jogging through a tropical rainforest, proposing a toast on the terrace of their luxury penthouse or sailing their yacht past an illuminated skyscraper. „You cannot find such real estate anywhere else in the world“, emphasized the manager – a view incidentally shared by his competitors, who are more appalled than enthused.

Anyone with a view of Athens from above will quickly understand why investors never run out of superlatives to describe this area. The city airport, built in 1938, was practically cut out of the city – its size is about one third of Athens. Hellenikon is roughly three times the size of Monaco and has several kilometres of coastline and beach. Such an open area by the Mediterranean Sea, in one of the most densely populated cities in Europe – Mr. Athanasiou can hardly believe his luck. The airport was in operation until 2001, and its future utilisation has been fought over since its closure. The result will disappoint many and make a few very rich indeed.

Much grass is currently growing in the Mayfair of the future. The area is enormous and difficult to manage. The terminal buildings are still intact, the runways serve as roads, and beside it are sports facilities. Some of them are still in use, the rest are in ruins. Basketball, Softball and Hockey stadia were built here especially for the Olympic Games in 2004. A few kilometres away the old, discarded pipes of the now dismantled Olympic canoe and kayak course are rotting away. Lamda wants to build a water park here. The beach lies behind the building.

Video: How Hellenikon looks like today

Here awaits Fereniki Vatavali, who works for the local mayor; she is furious. For ten years the population was promised that the area would be converted into a park. Even today, Ms. Vatavali is still fighting for this idea; she has planted 1,500 olive trees with other activists. Not because she believes she can delay the inevitable, but as a symbol for an alternative future that could have been.

It was a process with many stages that resulted in the sale to Lamda. The plan to keep the entire airport site as a park has long been dismissed. Back then, Spiro Pollalis, professor for town planning in Harvard, was involved. Together with his students, he developed a plan for the use of the site, fashioned as a seminar paper. The government liked the draft so much that they appointed him as head of the company that still manages the area to this day. Prof. Pollalis asked: „What does this city need?“ Athens is densely populated, polluted, scarcely green and with too few businesses unconnected with tourism. Hellenikon was a huge opportunity for urban development. Prof. Pollalis wanted to preserve one third of the area as a park, with the rest earmarked for apartments; a few hotels were also planned, as well as an area for offices and hospitals.

In 2011, Prof. Pollalis released an estimate that the land was worth at least €1.239 billion. Greece’s Mayfair was not supposed to come cheap. But then there were differences of opinion he did not want to talk about in public, and he left the state owned company. A more recent estimate, commissioned by the trust fund, valued the site at no more than €700 million.

Vatavali at the public Hellenikon beach (photo: ES)

Then the bidding process commenced. Nine investors had initially sought to buy the property, but, one after the other, they bailed out. Greek newspapers reported that the invitation to tender had been unclear; some suggest that this had been intentional. In the end, only one bidder remained: Lamda Development. More than half of the company belongs to private banker Spyro Latsis, one of the richest and most influential men in Greece. He had joined forces with even wealthier investors – Fosun, one of the largest private Chinese investors, and the Al Maabar fund from Abu Dhabi. He will need a lot of money; Lamda estimates the total cost of the project, including development and management, to be €8 billion.

Lamda Development acquired 30 percent of the site and obtained a concession for the remaining 70 percent for 99 years. The purchase price of €915 million will be paid over a period of ten years. The actual purchase price, converted to the present value, is just €577 million, just about half of Prof. Pollalis‘ estimate. Nothing more could have been made of it, according to the former head of the trust fund Konstantinos Maniatopoulos. Lamda was simply the only bidder.

To make Mayfair really profitable, the rules were even changed for Lamda. Although it had initially been stated that the buyer had to keep and develop the site in one piece, the company is now allowed to split its two million square metres acquired on a permanent basis into smalls units and sell them on. A huge business coup. Greeks are wondering: Why didn’t the government do this itself? Lamda can now wait for the market to recover before selling.

Hellenikon is no longer an urban development project, if it ever was one. It is a private real estate deal. It is an investment that could make some people incredibly rich. Since the sale – although not all formalities have been wrapped up yet – the Greek government has no more say in the matter. It will get a share of the profits, but not until the investors have recovered their expenses. And that can take a while. For the investors on the other hand, the deal has already been worthwhile. Both the shares belonging to Chinese investor Fosun and those held by Lamda have since increased significantly in value. In July, the U.S. investor Blackstone bought into Lamda to the tune of millions of euros. But in September the greek court of audit put the transfer on hold – officially because of “technical reasons”. Some say, the court isn’t amused about the government changing rules in Lamdas favour. But the HRAF is confident the transfer will not be blocked for long.

When asked if they had already spoken to Athens about what the city needs, Athanasiou looked up from his notepad in surprise. „No, we have not spoken to anybody yet. We will do that soon.“ The master plan, however, is already in place. The park will make up a third of the area, to comply with the minimum legal requirement. The hospitals have become cosmetic surgeries and the highlights are a giant aquarium and a residential ocean-view skyscraper. This is a genuine Mayfair.

The Water works – How troika is pushing water privatisation

One man who has been going on and on at people for the last few weeks can hardly believe what has happened. Kostas Marioglou is speechless. It is May 18, 2014 and 213,000 inhabitants of Thessaloniki have voted against the privatisation of the waterworks. Given a voting turnout of around 40 percent, this is an almost unanimous no (98.02%). Mr. Marioglou has won.

And it had not looked good at all just a few days earlier: Mr. Marioglou was sitting alone in the community centre of a working-class district in Thessaloniki. He had set up a projector beside him and even brought microphones up on the hill overlooking the city, in case the public became too loud for anyone to follow proceedings. But in the end, only five people turned up. And they only wanted to pocket a few flyers and be on their way. Mr. Marioglou turned off the projector and asked quietly: „How can I possibly induce people to get involved?“

Mr. Marioglou has long been fighting against water privatisation in his hometown. He put up posters and tried to convince people from street booths: convince them that selling the waterworks would cost many jobs rather than create new ones, that water prices would go up while the quality went down. Because in Europoly, the rule is just as in Monopoly: once the waterworks have been bought, the state must pay for its use every time it lands on the square. Mr. Marioglou has quoted examples of failed divestments from France, London and Berlin. He was once the trade union chairman at EYATH, Thessaloniki’s waterworks. The state has a 74 percent stake in the works and wants to sell 51 percent. Finally Mr. Marioglou set up a pressure group to enable him to buy the waterworks himself.

Marioglou’s „Initiative 136“ has calculated that if €136 is paid per person for every water connection in Thessaloniki, the waterworks can be bought and run as a co-operative. But it proved a slow process, because water privatisation is not as sensitive a subject in Greece as in other EU nations. The price of water in Greece is among the lowest in Europe. Then the trust fund excluded the pressure group from the bidding process; the favourite to succeed is reported to be the French company GDF Suez, which already owns around 5 percent of the waterworks. For this French company, the name of the game is „the more waterworks, the more profit.“ GDF Suez, one of the largest water companies in Europe, is even said to be interested in Athens‘ waterworks.

Kostas Marioglou and helpers (photo: ES)

So somehow Marioglou and his colleagues were able to induce people to vote after all. And now, several months after this victory in the referendum, things are looking good for opponents of privatisation. It is true that the Greek government did not acknowledge the referendum, just as they had announced. But the Greek supreme court decided shortly thereafter that the transfer of shares in EYDAP – the country’s largest waterworks, located in Athens – to the trust fund was not legal. The judges justified their ruling by claiming the decision to privatise would „compromise public health.“ The state is going to get back their shares from the fund. The situation in Athens is similar to that in Thessaloniki, even if preparations for privatisation are not quite as advanced there. The search for a potential buyer of government shares has since been officially put on ice – even in Thessaloniki.

Inhabitants of Thessaloniki could learn from Portuguese communities what can happen if privatisations are enforced. There, the system is regulated in a slightly different way from Greece. At the local level, communities can already enter into contracts with private firms, so long as it just involves the distribution of water. However, water purification is still controlled by the state – at least until now. The government-owned company „Aguas de Portugal“ may not directly be on the Troika’s privatisation list, but it is to be restructured and empowered to „enter into licencing agreements with private companies.“ That is how a PR woman at Aguas de Portugal put it. So the company would remain state-owned while the waterworks are virtually run by private firms.

Miguel Costa Gomes, mayor of the small community of Barcelos, wants to prevent this at all costs. This is why he has travelled especially from the north of the country to Lisbon. It was important to him to note that he was no „leftie“ during a meeting in a swanky hotel lobby – rather he was himself an entrepreneur. But that secret water privatisation thing, he thought that was terrible. He said his home community had entered into a contract with a private water company under his predecessor. Although his townspeople have been using on average 68 litres of water a day for years, these contracts guarantee an average daily water consumption of up to 165 litres. „I have no idea how anyone could put such a figure into the contract“ grumbles Mr. Costa Gomes today. He would like to terminate the contract, but Barcelos now officially owes the company €165 million.

In Lisbon, the mayor of Barcelos met his colleague from Pacos de Ferreira, a community half an hour from Barcelos. Humberto Brito has a court hearing coming up. He wants the courts to get his community out of a water contract, because, here too, there is not enough money to buy it back. In the last six years, water prices in his community have gone up by 400 percent. It is as though the operators were playing by Monopoly rules: anyone who lands on the Water Works square must pay four times the number thrown with the dice. Brito used to be the leader of the local anti-privatisation compaign before the people voted him mayor. They publicly complain about having to pay almost 20 percent of their income for water.

„This can affect all of Portugal if we do not stop privatisation“ warns Miguel Costa Gomes. He says he does not understand why water privatisation is being forced through in affected countries despite being so controversial in Europe otherwise. And what does the European Commission say? They are officially staying out of the matter. „There is no pressure from the EU to privatise the water sector, not even in programme countries. The Commission is taking a neutral stance“ said a speaker for the Commission. Yet the Troika’s audit report on Portugal says that „opening up water operations to private capital and management“ is being considered. In Greece, the Troika has already begun to set up a regulatory authority as a precaution. This authority is meant to monitor private management of waterworks.

The Electric Company – How china is buying portugal’s Energy sector

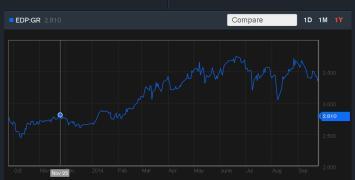

AOn his last trip to China, he was even accompanied by the president. Eduardo Catroga, chairman of the supervisory board at Energias de Portugal (EDP), one of the largest energy providers in Europe, was in his Lisbon office eating breakfast, having just got off the plane. It had been a nice journey, with a large delegation. This is because even Portuguese president Anibal Cavaco Silva knows too well that the influence of Chinese investors on Portugal is growing.

They are among the main buyers in privatisation programmes and are especially interested in the energy sector. Portugal’s energy firms present them with a window to Brazil and the lucrative renewable energy market.

Just like the Water Works previously, the deal with Europoly’s Electric Company is simple: The state sells its company and pays for its services in the future. Whenever the state steps on the square on the playing field, it pays. The Portuguese government used to run two large energy firms. EDP was responsible for power generation and REN was responsible for running and maintaining the networks. EDP was already partially privatised in 1997 while REN was not initially intended for sale. Without the economic crisis, the electricity grid would probably still belong to the state. The Troika’s contract at least stipulated that: under no circumstances could both go to the same owner.

When the Troika came, the government still held a 21.35 percent share in EDP. It sold this stake to the state holding company China Three Gorges Group (CTG), which runs the world’s largest hydroelectric dam on the Yangtzee river. As a consequence CTG is by far the biggest shareholder in the electricity company. China Three Gorges outbid the competition – including German energy firm E.on – with a €2.69 billion offer. At the time, this price was 52 percent over the actual share value. It was a deal that contributed significantly to Portugal’s ability to surpass its privatisation goals, let alone meet them. Jubilation all round. At least just this once, the crisis seemed insignificant.

Or did it? Before he had even finished breakfast, a beaming Eduardo Catroga related how company shares had risen sharply since the sale. The buyers were said to be extremely happy. The markets have recovered since 2011. Profits are now flowing to China

And the Chinese government doesn’t do things by half: the Portuguese government’s shares in network operator REN were also acquired by a state fund. The State Grid Company paid €387 million for 25 percent of the shares. This makes the Chinese government the most important stakeholder of both the power generator and the network operator – which certainly makes co-operation easier between two firms, which are actually separate. Meanwhile, IMF representative Albert Jäger denies that the twofold Chinese involvement is a problem. After all, the buyers are two different companies, and it’s only a partial privatisation.

Since then, the prosecutor’s office has stepped in. They doubt whether the entire sale was legally sound. This is because the head of investment bank BESI, which represented both Chinese companies in the negotiations, is known to have made nine phone calls to Portuguese Prime Minister Passos Coelho during the heated negotiation phase about REN. Moreover, he was in close contact with state banker Jorge Tomé, who was evaluating bids on the government’s behalf. Investigative authorities are now checking if Chinese company State Grid could have obtained insider information this way, which would have given it advantages over the competition. The telephone calls had been intercepted, as investigations were ongoing against the investment bank in another matter.

The Go-Square – Portugal’s Banking Scandal and the Despot’s Daughter

The GO Square is extremely popular with players. Passersby do not have to pay, but can pocket extra cash. Portugal transformed one of its banks into a GO Square for investors. But one thing at a time: Paulo Pena looked up and grinned. „Ready?“ he asked. Pena was sitting in a café on the banks of the river Tagus in Lisbon and trying to explain a bank scandal over a cup of coffee. He is a journalist and has recently published a book entitled „Power Games: How Portuguese Banks caused the debt crisis.“ The book, all about blackmail and political factions, became a bestseller. The bank currently in question is not even significantly large. But when the crisis began in 2008, the Banco Portugues de Negocios – BPN for short – was deeply involved in real estate deals. Several of their borrowers are said to have been high-ranking politicians. The government decided to nationalise the BPN, thus saving it from bankruptcy.

Nowadays many experts say the rescue operation was a big mistake. Even the government admits it indirectly. But at the time the fear was that bankruptcy would have grave consequences for the economy. Even several years later under the Troika regime, the Portuguese government again decided against orderly default. An initial attempt to sell the bank for €180 million failed in 2010. Nonetheless, the conservative opposition in particular, who would shortly go on to form a government, lobbied for a swift re-privatisation in negotiations with the Troika.

The treaty between the Troika and Portugal contains details that are highly uncharacteristic for what is otherwise an extremely vague document. The BPN was to be sold within three months, at no minimum stipulated price, and the Portuguese government should moreover take on all non-performing contracts burdening the bank. On the basis of such a publicly articulated negotiating position, potential buyers were really able to make any demands they wanted. It is almost like a Europoly player putting down the dice, staying on the GO Square and proceeding to collect money with every move.

Initially, nine companies were supposedly interested in the BPN, among others Brazilian, Spanish and Argentinian banks. But finally only one serious interested party remained: the Banco BIC Angola, the fourth biggest bank in the southern African state. At this time it already had a branch in Portugal, the BIC Portugal, which primarily finances trade business between Portugal and its former colony.

The most important owners of the BIC, each holding 25 percent, are Américo Amorim, the Portuguese cork billionaire and Isabel dos Santos, daughter of the Angolan president. The bank BIC was only founded in 2005, and its biggest borrower at the time was the Angolan government with €450 million. Isabel dos Santos has the nickname of „the Princess“ in her home country. Forbes, on the other hand, calls her rise to fame a “a rare window into the same, tragic kleptocratic narrative that grips resource-rich countries around the world.” Ms. dos Santos makes her money primarily with oil and diamonds. While most Angolans have to live on less than two dollars a day, her fortune is estimated at $3 billion.

The BIC has the best possible political contacts. BIC Managing Director Luis Fernando de Mira Amaral is a former industry minister and was also Vice President of the state-owned bank, CGD, which saved the BPM from bankruptcy. According to Portuguese media he had at least two private meetings with Prime Minister, Pedro Passos Coelho, during the negotiations.

Just before the sale, the Portuguese government had to pump another €600 million into the BPN, so the bank was able to fulfil the Europe-wide requirement in terms of equity ratio. An investigation committee of the Portuguese Parliament later estimated that the nationalisation and re-privatisation of the BPN has cost Portuguese taxpayers around €6 billion up to now. The Angolans purchased the BPN for €40 million.

EU Commissioner Joaquin Almunia maintains to this day: the deal was supposedly the only possibility to save Portugal’s banking sector from destabilisation. According to the former Secretary of State and today’s Finance Minister, Maria Luis Abuquerque, the only alternative to reprivatisation would have been the bankruptcy of the bank. This would reportedly have been even more expensive at €1.5 billion.

“It was a gift”, grumbles one politician who took part in the Troika negotiations. It is a fact that the Portuguese are still have to pay for the deal. There are secret clauses of which, up to now, only a few have been revealed. One of them, according to Portuguese media, is that the new bank BIC now offers less favourable conditions than the BPN did formerly. The difference to the high interest rates, still accorded to old clients, is paid by the state. That alone cost €8 million in the first six months of the year 2013.

The decidedly shady role played by Angola in international financial transactions is something no one at the Troika wishes to comment on. “We live in a globalised economy,” says IMF representative Mr. Jäger. If the BIC prevailed in the bidding procedure, then it would have to be assumed “that it fulfilled the objective criteria.” This is despite the not particularly good experiences made by the Portuguese government with the Angolan financial sector: the now defunct bank “Espirito Santo”, propped up for years with countless billions, gave €5.7 billion in credit to Angola in recent years. That money disappeared. Another banker and confidant of the Angolan ruling family has to go to court in the U.S.A., suspected of money laundering.

The Spoilsports

Resistance is forming

Europoly brings many players great wealth and drives others into bankruptcy. Spoilsports therefore demand fairer rules. They ask the Troika: Why are the crisis-ridden states being put under so much time pressure? Why didn’t everyone wait with the divestment projects until the market recovered? Why is everything being done to create a bargain basement for investors? Resistance is forming. The third chapter is about those, who want to change the game.

THE SPOILSPORTS – who tries to change the rules?

- Troika

Loans - €270b

- Privatization

Goal until 2016 - €11b

(2014) - €50b

(2011) - reached

- €4b

There are Europoly players whose idea of rewriting the rules is to scrub the game board clean with their sleeve and start again. But the Troika functionaries have not been like that so far. They want nothing to do with the problems caused by privatisations. “We do not want to play the role of super snoops”, is how Thomas Wieser, the head of the Eurogroup, justifies this stance. “Yes, perhaps there should be more control in one or the other area, who can say for sure. But when just one bidder is in play, what are you supposed to do?” Apparently, keeping to the rules of the tender is the most important thing.

The national governments have absolutely no interest in controversial discussions with the international press. The Portuguese finance minister has no time to answer questions, not even in writing, and the same applies to her deputy. In Greece, the trust fund head, Konstantinos Maniatopoulos, initially gave “Der Tagesspiegel” an almost 2 hour-long interview. But then he was not able to release it for publication. In a surprise move, the new Financial Minister then fired him. In the interview, one of Mr. Maniatopoulos’ justifications for his actions was that waiting would have cost more than a quick sale.

It was the worst possible time in the world to start a privatisation programme. Costas Mitropoulos, former manager, HRAF

Other former trust fund employees are more critical. Costas Mitropoulos, former manager of the trust fund, now says: ”It was the worst possible time in the world to start a privatisation programme.” He goes on: “The economy was going down fast. Normally you shouldn’t privatise in the middle of a deep crisis. But the Troka didn’t realise in the beginning that it was not a question of price. Simply the market wasn’t willing to buy at any price.“ It is the fund’s clear mandate to sell as quickly as possible. Mr Mitropoulos now believes that this mandate should be changed: “ Personally I would prefer a State wealth fund with a different mandate. Not to privatise assets but to run them, restructure them and at the end selling them.“ For example, some objects could be leased out. „Each year a certain amount would be payed to the state by the State wealth fund.”

There are politicians who would like to start the game all over again and play it differently. At a national level they are usually to the left and right of centre, as both in Greece and Portugal the major parliamentary groups support the programmes. One politician who grumbles about Greece’s “closing-down sale” is a Member of Parliament from the Greek leftwing party Syriza, Zoe Konstantinoupoulou: “It is humiliating for Greece to have to sell all that off dirt-cheap”, she says. She has found her own explanation: “The only reason for the privatisations is to satisfy special business interests – not the public interest.”

One man who wanted to take his protest right up to the EU level is Kriton Arsenis. The 37-year-old is sitting at one of the small tables in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. It is early in the year and Mr. Arsenis has little time. He is fighting for a ticket for the EU Parliament, where he has had a seat for the last four years. But this is not being made easy for him, because in protest against the planned privatisation of the waterworks of his hometown Thessalonica, he resigned from the PASOK Parliamentary group, the party of Deputy Prime Minister Evangelos Venizelos. He is furious at the fact that environmental regulations are being ignored on a massive scale for the privatisations. “They are attacking me aggressively on television, saying I am obstructing the economy”, he says. Mr. Arsenis, the spoilsport, was not elected to Parliament in May.

- Troika

Loans - €78b

- Privatization

Goal - €5,5b

- reached

- €9b

There are economists in Portugal who want different rules of the game. José de Caldas, from the “Observatorio da crise” at the University of Coimbra, has opened an office with his colleagues in Lisbon. “They let us speak”, says the economics professor about government politicians, “but they don’t really listen to us”. He and his team are trying to document what the crisis is actually changing in the country.

“What use is a debt reduction of a few percentage points?” asks Prof. de Caldas. That is a criticism of the fact that the sales proceeds in Europoly flow directly into debt repayment. The amounts involved represent only a tiny amount of the size of the debt which has continued to rise for other reasons. The missing revenues from profitable state companies on the other hand, have created massive gaps in the budget. Because the game goes like this: the state sells and rents back. That costs money.

It is humiliating for Greece to have to sell all that off dirt-cheap! Zoe Konstantinopoulou, Syriza

The level of the programme countries’ debts is indeed stiflingly high. At the end of Troika operations Portugal’s debt was 129 percent of gross domestic product, in 2011 it was just 108 percent. In Greece it is about 175 percent of GDP in 2014, at the beginning of the programme it was 148 percent.

The spoilsports and critical economists get international support. „Privatization is not always a bad thing. But there were a lot of fire sales that were really unnecessary“, says Paul Krugman, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2008. „There was a lot of private gain involved here. The profits were privatized and the risks were socialized. Or the losses were socialized.“ He sees some similarities between crisispolitics in the US and in Europe: „Some of the politics come from the fact that bankers tend to be impressive people. They are obviously very successful, they are very rich, they tend to be kind of smart. You have a room full of bankers and they seem like men of the world who really know what should be done.“ He goes on: „Very hard to have some labour leader or some academic economist in his badly fitting suit, argue against these very impressive people.“

The next opportunity to change anything in the present system in Greece would probably be when the Troika program officially ends in 2016. But not much points to change so far.

In Portugal, the Troika mission officially ended early in 2014. In the strategy paper, the government describes the privatisations as one “of the most successful aspects” of the entire stabilisation programme. Incomplete privatisations will reportedly be continued.

In Cyprus, where the game first began, the Troika recently showed that it is not prepared to negotiate about the rules of the game: the law to legally prepare coming privatisations, was rejected by Parliament. The Troika’s reaction to this was to threaten to withhold the next credit instalment. The members of Parliament had to vote again. At the second attempt the law was passed. In other words: if you’re not playing the game correctly, you have to throw the dice again.